About the Blue Note label

A lot of books and articles have been written about the Blue Note label, but still I would like to make a small contribution to one of our favorite and most respected labels. At the end of December 1938, a German immigrant and jazz lover Alfred Lion visited the now famous “From Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall, hosted by John Henry Hammond. Just two weeks later, Lyon and his friend Max Margulis had already booked a time in the studio to record some of the performers involved in the concert. Thus began the history of the Blue Note label.

Margulis formulated the main credo of the label, which Blue Note strictly followed over the following decades, namely: “Blue Note was created with the aim of doing everything possible to uncompromisingly present jazz and swing as the main musical styles with which we are working”. Margulis himself, Lyon, and many jazz musicians of that time felt that the main “jazz” labels did not convey the whole variety of jazz. Blue Note has been able to record many bebop artists who are now recognized as recognized masters of the genre – Tadd Dameron, Theodore “Fats” Navarro, and many others.

Very quickly, Blue Note became an innovative pioneering studio in the world of jazz music, followed by other independent labels – Prestige, Keynote, HRS. It was Blue Note who came up with the so-called “night recordings” – she gathered musicians at three to four in the morning, right after their concerts in night clubs, at the peak of boiling energy and splashing emotions over the edge. Unlike its rivals, Blue Note always paid for session recordings in advance, guaranteeing that the musicians would play with full dedication.

Years passed, but the Blue Note image remained unchanged – the label still paid much more attention to the quality of recording and release than commercial side of the matter. This has repeatedly put Blue Note on the brink of bankruptcy. Many performers who are currently considered pioneers of jazz, like Thelonius Monk, began releasing their recordings on Blue Note, and in commercial terms they failed completely. When the record industry switched from 78 rpm to 10-inch LPs in 1949, and then to 12-inch LPs in 1954, Blue Note, which was already experiencing serious funding problems, lagged behind technically, and the transition to the modern formats for that time almost ended in complete ruin for her.

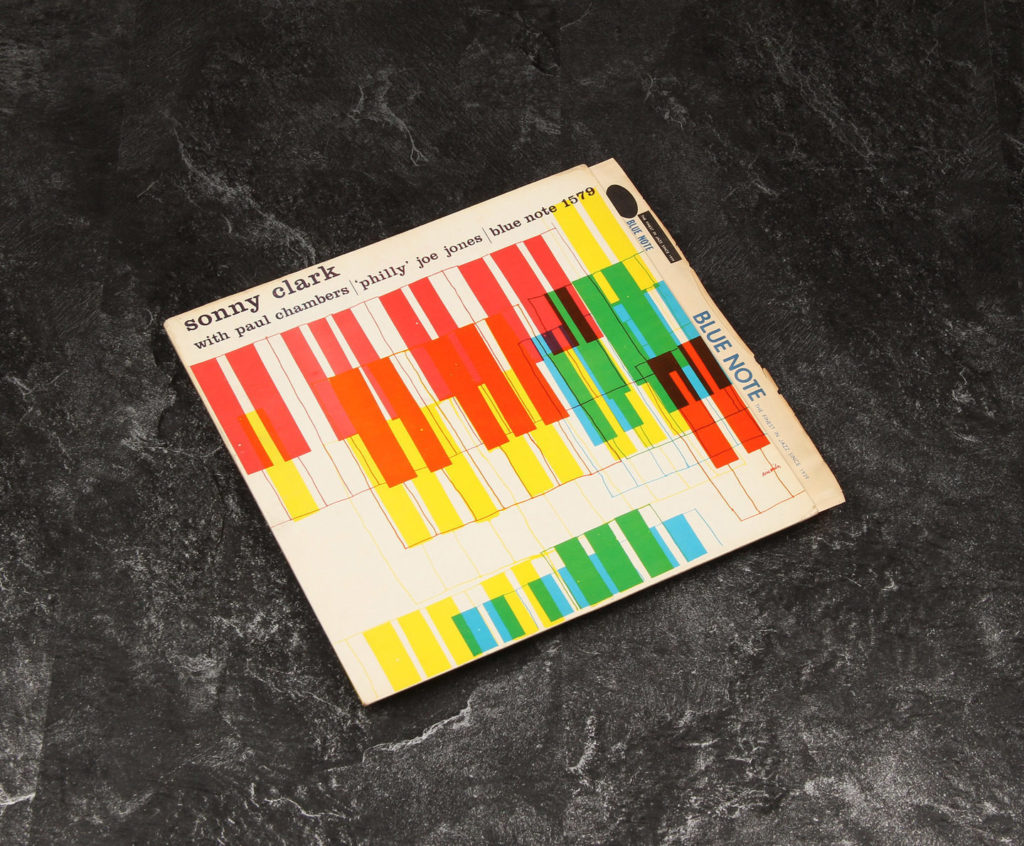

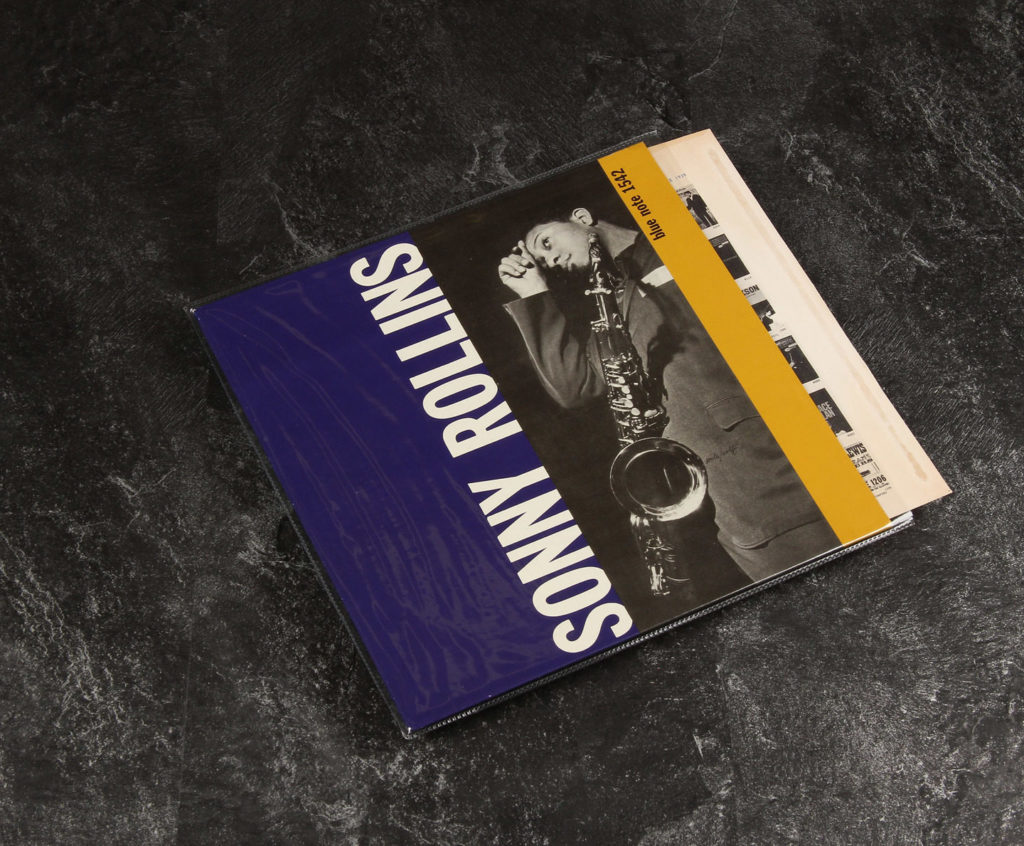

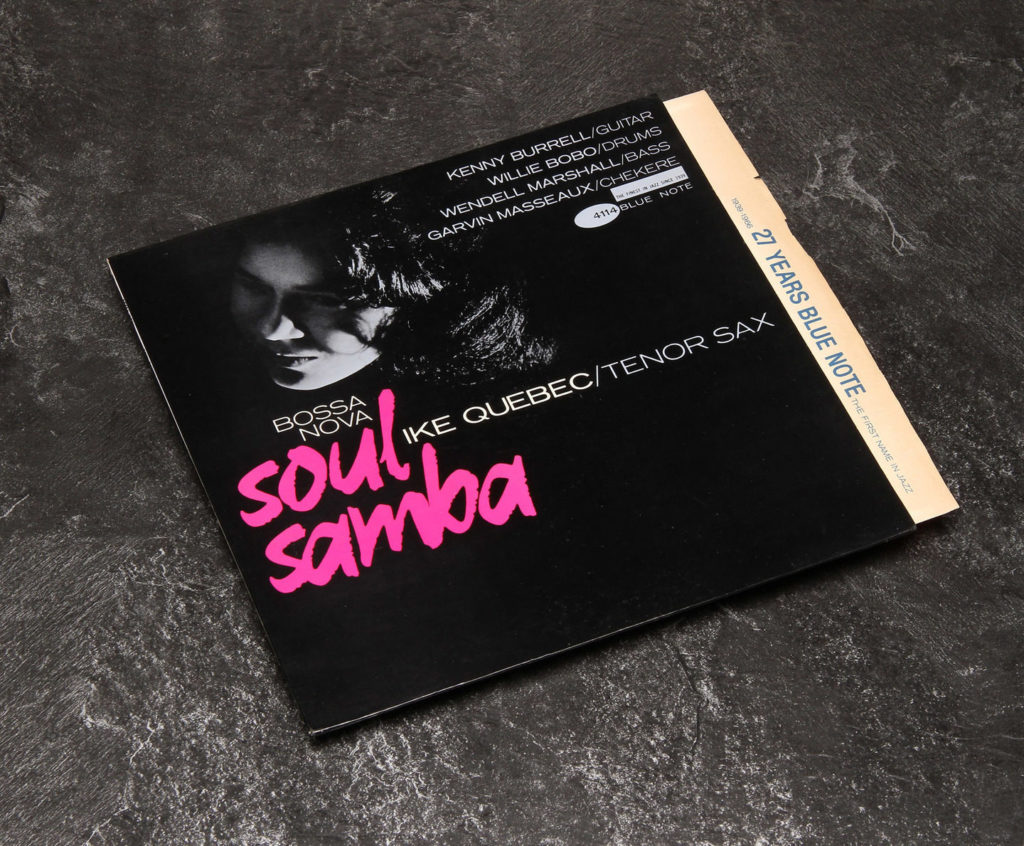

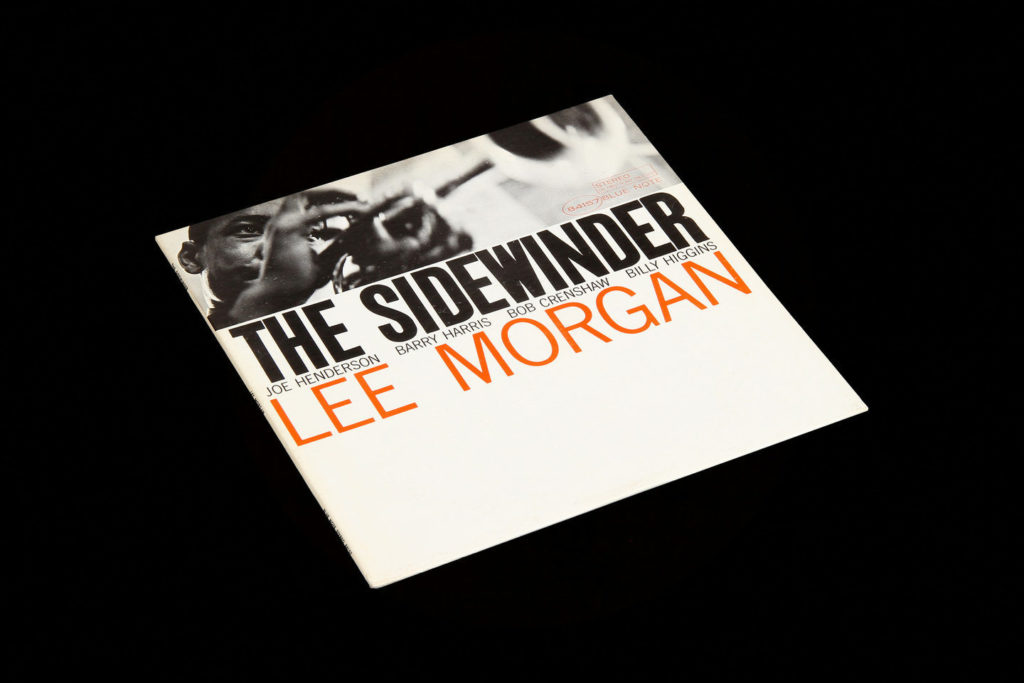

Nevertheless, in the 1950s, Blue Note finally achieved real success – all of her undertakings and innovations, combined in a single process, began to bear fruit. The label was drafted by sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who developed his own recording technique in which jazz sounded exactly as it should have been – energetic, full, rich and vibrant. Blue Note also hired Reid Miles, a renowned designer and photographer, to design the envelope for vinyl records. Leonard Feather, Ira Gitler, Robert Levine, Nat Hentoff, and others wrote texts for inserts, and Lyon’s business partner, Francis Wolff, took photos. Currently, holding the original envelopes in your hands, you are amazed at how high the quality of printing was.

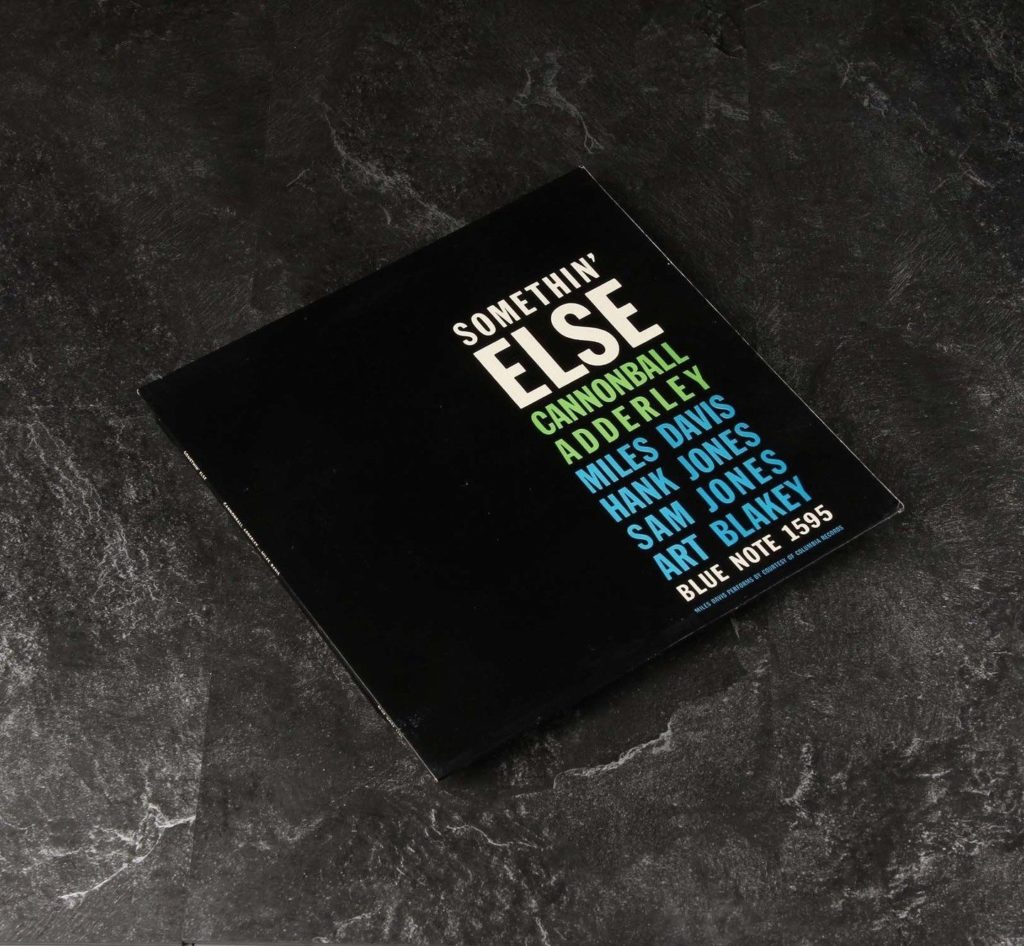

Almost at the same time, Blue Note began recording Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers, which, in addition to Blake, included Horace Silver, Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham, Doug Watkins. The Jazz Messenger turned to blues and gospel, with the goal of performing for a wider audience, understandable, but at the same time, original jazz. Blue Note’s “Blue Train” (1957) by John Coltrane and “Somethin’ Else” (1958) by Cannonball Adderley are also considered iconic Golden Age recordings.

But despite all the successes, in the 1960s the sunset of the cult label began. After hits such as “The Sidewinder” by Lee Morgan and “Song for My Father” by Horace Silver, distributors began to hold back money for Blue Note records, using it to blackmail in order to lure more and more hits out of the studio. Unable to survive the long breaks between hit releases, Lyon was forced to sell Blue Note to Liberty Records in 1966. Many employees and managers from the old Blue Note team stopped working on the label, as they were replaced by clumsy bureaucratic commissions.

With the advent and development of progressive rock in the early 1970s and the general decline in the record industry that began, Blue Note released it seemed that his last record was “Silver ‘N Strings Play the Music of the Spheres” by Horos Silver, which was released in 1981. But in 1985, the music giant EMI returned Blue Note from oblivion, appointing her new manager Bruce Lundvall, a huge role in this event was played by the efforts of Michael Cuscuna and Charlie Lourie. From that moment on, the revived Blue Note label continues to release new jazz records, and thanks to artists such as Norah Jones, it has achieved commercial success.